Haiti’s army wants recruits to fight gangs, a rare job opportunity for young people

The announcement that Haiti’s military wanted recruits crackled through a small radio perched on a street stall in downtown Port-au-Prince where Maurenceley Clerge repairs and sells smartphones.

It was early morning, and the 21-year-old paused, eager to hear the details. He envisioned earning enough to afford his own food and rent. Two weeks later, he completed the required paperwork and stood in line with hundreds of other Haitians under a brutal sun for the chance to join up.

“It’s the moment I have been waiting for,” said Clerge, who stays with a friend who also provides him with food. “I want to serve as a citizen of this country and also to move up and upgrade my life.”

Thousands of young Haitians are jumping at the chance to become soldiers as widespread gang violence creates a rare job opportunity in a deeply impoverished country where work is scarce. Brushing aside the possibility they could be kidnapped, tortured or killed, Haiti’s youngest generation is answering the call of a government seeking to rebuild a once-deeply reviled military, reinstated just years ago with the aim to crush gangs.

“I thought about it a lot because I know that being a soldier requires a lot of sacrifice,” said Samuel Delmas, who recently applied. “Everything that you’re doing is risky.”

A journalist. An army sergeant. An 80-year-old patient. Haitian human rights group details gang toll

A Haitian human rights group releases a report detailing the violence unleashed by gangs who kill, rape and maim with impunity amid a political vacuum.

The 20-year-old is taking computer repair courses but doesn’t have a job. He heard about the recruitment via a Facebook group.

Gangs forced Delmas and his family to flee their home two years ago, with only enough time to grab a handful of clothes amid a barrage of gunfire, he said.

“I want to protect citizens who are on the run like me,” he said.

Life in Port-au-Prince becomes a game of survival, pushing Haitians to new limits as they scramble to stay safe and alive while gangs overwhelm police.

‘Most young kids are not working’

Haiti’s government has not said how many soldiers it aims to hire nor how many have applied so far, but documents published online by the Defense Ministry show that at least 3,000 people were selected in mid-August and asked to submit documents as they await physical and mental tests.

If all were hired, that would more than double the force strength of 2,000 of early last year.

About 60% of Haiti’s nearly 12 million people earn less than $2 a day, with inflation soaring to double digits in recent years.

“Most young kids are not working,” said Emerson Celadon, a 25-year-old mechanic who applied and was selected for the next round. “I was making some money, but … that is still not enough for a family of four.”

It’s not clear how much soldiers earn. Defense Minister Jean-Marc Bernier Antoine did not return messages for comment. However, Celadon said friends in the army told him they make about $300 a month.

On a recent afternoon, Celadon joined hundreds of mostly young men lined up outside a former United Nations base, a yellow envelope under his arm, waiting to take the first of several required tests to join the army.

The military’s dark past

Haiti’s armed forces were once widely feared and hated, with soldiers accused of horrific human rights abuses. The military organized several coups in the second half of the 20th century, even after so-called “dictator for life” François Duvalier diluted its strength.

After the last coup in 1991, to oust former President Jean-Bertrand Aristide, the government disbanded the armed forces in 1995. At the time, there were some 7,000 soldiers.

“The decision to demobilize the army … proved to be one of the most catastrophic decisions in the country’s history,” said Michael Deibert, the author of two books about Haiti. He noted that, as a result, the first generation of politically aligned gangs took root in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

“They stepped into a security void left by what would have been a security force, one whose role the Haitian police have never been fully able to assume,” Deibert said.

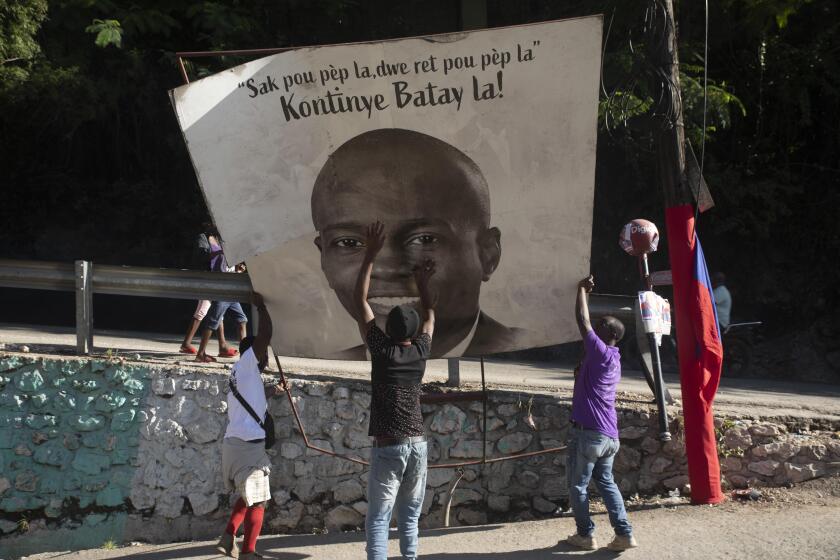

After the army was disbanded, the government created the Haitian National Police and the Coast Guard, which were bolstered by the arrival of U.N. troops. Once the U.N. ended its peacekeeping operations, the army was reinstated in 2017 by President Jovenel Moïse, who was assassinated in July 2021.

Since then, the military has played a small role in fighting gangs and protecting top government officials. But as gang violence surged in the years following Moïse’s killing, former Prime Minister Ariel Henry announced in March 2023 that he would mobilize all security forces. At the time, the armed forces had some 2,000 soldiers who were trained by experts in Mexico, Colombia and Argentina.

Despite the announcement, the military’s role continued to take a backseat to police until recently.

A year has passed since President Jovenel Moïse was assassinated at his private home.

A new army

Gen. Derby Guerrier was sworn in as the new armed forces chief on Aug. 20, just days after a massive recruitment for new soldiers ended. “Close ranks!” he ordered soldiers and officers during a brief but energetic speech as he demanded that they help Haiti restore peace.

More than 3,200 killings were reported across Haiti from January to May, with gang violence leaving more than half a million people homeless in recent years, according to the U.N.

A new report from the U.N. migration agency says surging violence in Haiti from clashes with armed gangs has displaced nearly 580,000 people since March.

In coordinated attacks earlier this year, gangs seized control of more than two dozen police stations, closed down the main international airport for nearly three months and stormed Haiti’s two biggest prisons, releasing thousands of inmates.

Newly appointed Prime Minister Garry Conille has warned that the armed forces face “colossal challenges” while pledging to modernize the military and invest in communication and surveillance technologies. He also said he would improve military infrastructure, housing and healthcare for soldiers and their families.

“A soldier … whose family is safe and well cared for is a soldier who is more determined and focused,” Conille said.

The military is expected to work with Haiti’s police and a U.N.-backed mission led by Kenya, which has sent about 400 police officers to Haiti so far to help quell gang violence. More police and soldiers from countries including Benin, Chad and Jamaica also are expected to arrive in coming months for a total of 2,500 foreign personnel.

Celadon, the mechanic, hopes he can work alongside them and help change Haiti.

“I would love to see the country like how I heard it was back in the day: a Haiti where everyone can move around freely, where there are no gangs, where everybody is able to work,” he said.

Associated Press writer Evens reported from Port-au-Prince and Coto reported from San Juan, Puerto Rico.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.