White House says prescription drug deals will produce billions in savings for taxpayers, seniors

Taxpayers are expected to save billions after the Biden administration signed deals with pharmaceutical companies to knock down the list prices for 10 of Medicare’s costliest drugs.

But how much older Americans can expect to save when they fill a prescription at their local pharmacy remains unclear, since the list cost isn’t the final price that consumers pay.

After months of negotiations with manufacturers, list prices will be reduced by hundreds — in some cases, thousands — of dollars for 30-day supplies of popular drugs used by millions of people on Medicare, including blood thinners, diabetes drugs and blood cancer medications. The reductions, which range between 38% and 79%, take effect in 2026.

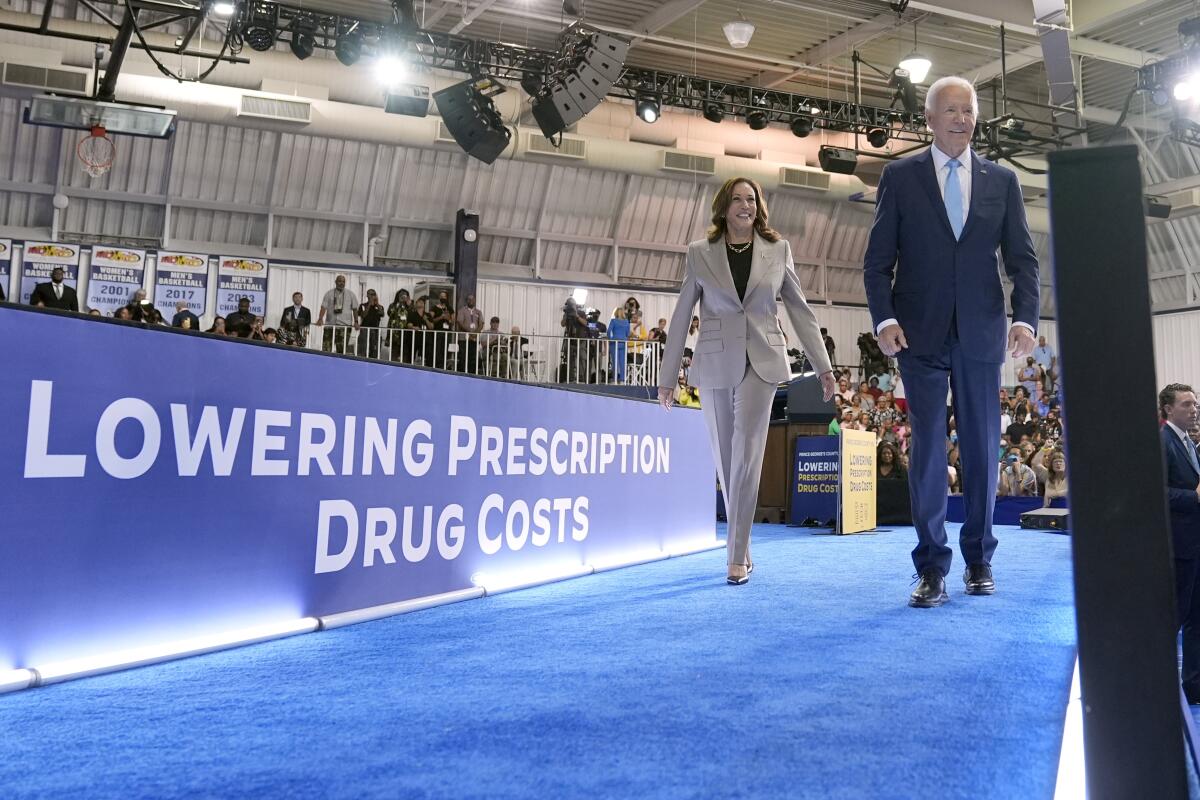

“I’ve been waiting for this moment for a long, long time,” President Biden said Thursday, during his first policy-oriented appearance with Vice President Kamala Harris since she replaced him as the Democratic presidential candidate. “We pay more for prescription drugs, it’s not hyperbole, than any advanced nation in the world.”

Taxpayers spend more than $50 billion yearly on the 10 drugs, which include popular blood thinners Xarelto and Eliquis and diabetes drugs Jardiance and Januvia.

With the new prices, the administration says savings are expected to total $6 billion for taxpayers and $1.5 billion overall for some of the 67 million people who rely on Medicare. Details on those calculations, however, have not been released. And the White House said it could not provide an average cost savings for individual Medicare enrollees who use the drugs.

That’s because there are a number of factors — including discounts and the coinsurance or copays for a patient’s Medicare drug plan — that determine the final price a person pays when they pick up their drugs at a pharmacy.

The new drug prices are likely to most benefit people who use one of the negotiated drugs and are enrolled in a Medicare plan with coinsurance that leaves enrollees to pay a percentage of a drug’s cost after they’ve met the deductible, said Tricia Neuman, an executive director at the health policy research nonprofit KFF.

“It is hard to say, exactly, what any enrollee will save because it depends on their particular plan and their coinsurance,” Neuman said. “But for the many people who are in the plans that charge coinsurance, the lower negotiated price should translate directly to lower out-of-pocket costs.”

Those savings won’t kick in until 2026. Until then, some Medicare enrollees should see relief from drug prices in a new rule starting next year that caps how much they pay annually on drugs to $2,000.

Harris, however, wasted no time Thursday touting the new drug deals, especially since no Republicans supported the law, called the Inflation Reduction Act, or IRA, and it barely passed Congress in 2022.

“In the two years since, we’ve been using this new power to lower the price of lifesaving medication,” she told the crowd.

Before dropping out of the race, Biden had made lowering healthcare and drug costs a key part of his reelection pitch. But the messaging failed to resonate deeply with Americans, in part because the savings have not had widespread reach.

Powerful drug companies unsuccessfully tried to sue to stop the negotiations. For years, Medicare had been prohibited from such deal-making. But the drug companies ended up engaging in the talks, and executives had hinted in recent weeks during earnings calls that they don’t expect the new Medicare drug prices to change their bottom line. Instead, they warned Thursday that the new law could drive up prices for consumers in other areas. Already, the White House is bracing for a jump in Medicare drug plan premiums next year, in part because of changes under the new law.

“The administration is using the IRA’s price-setting scheme to drive political headlines, but patients will be disappointed when they find out what it means for them,” said Steve Ubl, the president of the lobbying group Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America.

The criticism is ironic, health law expert Rachel Sachs of Washington University said. Drug companies have typically supported capping the price older Americans pay for drugs because the companies don’t eat the cost — insurers or Americans who pay premiums do.

“It makes it easier for patients to afford their medications. It expands their market. They make more money,” said Sachs, who helped advise the Biden administration on implementation of the law.

Seitz and Miller write for the Associated Press. AP writer Tom Murphy in Indianapolis contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.